Kinematics of Fluid Flow

Fluids are generally modelled as a collection of fluid “particles” (\epsilon = 10^{-9}m in size usually - per Fluid Mechanics textbook).

The motion of a fluid particle is determined by its inertia, shear stresses, and a gradient in the pressure field.

Shear stresses are your viscous forces; inertial forces are your inertial forces. Reynolds Number tells us how relatively important each of those forces are.

\textnormal{inertial forces} : \textnormal{viscous forces} \propto \textnormal{Re}

1 Definitions

Definition 1 (One-Dimensional Flow) Flow with one principal flow direction. Many common problems can be treated as problems of one-dimensional flow.

Definition 2 (Steady flow) A flow in which the velocity at a given point is not varying with time.

Definition 3 (Uniform Flow) A flow in which, at a particular instant, all points have the same velocity.

It’s very important to notice the difference between steady flow and uniform flow! Steady flow is a condition of flow which is satisfied over a period of time, but allows for particles to have different velocities. Uniform flow is an instantaneous condition of the velocities of the points. Flow can be steady without being uniform (imagine flow passing over an airfoil in a wind tunnel), and vice versa (oscillating wind velocities).

In FM2, we are dealing mainly with steady flows, where the following definitions converge to mean the same thing.

Definition 4 (Pathline) Line traced by a fluid element over time as it progresses through a flow.

Definition 5 (Streakline) Line joining the instantaneous positions of all particles which have passed through a given point, eg the line traced by a spot of dye in a flow.

Definition 6 (Streamline) A line across which there is no flow. The local velocity (vectors of the particles in a) flow is always tangential to a streamline.

You can have a streakline without being a streamline if the flow is turbulent: the dye breaks up into many paths. Again, for steady flow, these all mean the same thing.

Definition 7 (Streamtube) Although it sounds like a startup for watching livestreams, this actually refers to a bundle of streamlines in 3 dimensions, creating an invisible “pipe” through which flow does not cross.

2 Continuity Equation

Here we apply the principle of conservation of mass to a fluid system. Whatever mass goes into our system every second should come out every second. No ifs, &&s, || buts.

We define the volume flowrate Q as the volume of fluid passing through a given cross-section per unit time. Other symbols for Q include \dot{V} and little q.

The SI unit for Q, m^3/s, is often referred to as a cumec in civil engineering, when talking about the (volumetric) discharge of a river.

So we imagine our streamtube. Take a little cross-section perpendicular to the walls of the streamtube of area dA. If the flow is flowing at u meters per second, then all of the fluid within the streamtube within a length of u meters from the cross-section will pass through the cross section in one second. (We take a scale small enough to assume that this flow is uniform.) This means the volumetric flow is the extrusion with area dQ = u\, dA.

In incompressible flow, the volumetric flow rate is proportional to the mass flowrate. We assume that the liquid is of uniform density \rho. So the mass flowrate \dot{m} equals the density times the volumetric flowrate.

\dot{m} = \rho \, dQ = \rho \, u \, dA

So the total mass flowrate over an area A is

\dot{m} = \int_A \rho \, dQ = \int_A \rho \, u \, dA

2.1 Continuity Equation in Ideal Flow

With ideal flow in a pipe, velocity is constant across a cross-sectional area, so \int_A \rho \, u \, dA = \rho \, u \, \int_A dA = \rho \, u \, A

Since \dot{m} is constant, this means that the product \rho \, u \, A must be constant at all cross sections of the pipe. u_1 A_1 = u_2 A_2.

2.2 Continuity Equation in Real Flow

Here, the velocity varies across the length of the pipe. We take a mean velocity, \bar{u} = \frac{Q}{A}, and find that \bar{u}_1 A_1 = \bar{u}_2 A_2.

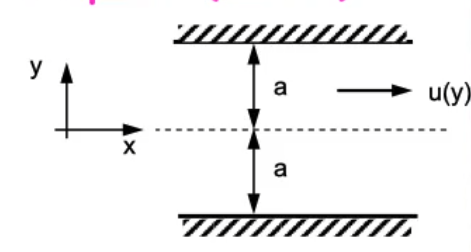

Consider laminar flow in a rectangular pipe, where u is parabolic with respect to y:

u(y) = u_{max}\left( 1 - \frac{y^2}{a^2}\right)

Let b be the length of the pipe’s cross-section such that by is the area of the pipe.

\begin{align} \dot{m} &= \int_A \rho \, u \, dA \\ &= \rho \, b \, \int_{-a}^a u(y)dy \\ &= \rho \, b \, \int_{-a}^a u_{max}\left( 1 - \frac{y^2}{a^2}\right)dy \\ &= \rho \, b \, u_{max} \left.\left(y - \frac{y^3}{3a^2} \right)\right|_{y=-a}^a \\ &= \frac{4}{3}\rho \, b \, u_{max} \,a \end{align}

The mean velocity \bar{u} is given by the mass flow rate over the area, so

\bar{u} \equiv \frac{Q}{A} = \frac{\dot{m}}{\rho}\frac{1}{2ab} = \frac{2}{3}u_{max}.