Power Systems

The present and future of the grid

I missed the first five minutes of this lecture.

Power systems use AC voltages and currents, with high voltages (hundreds of thousands) used to transfer power long distances.

The future of the grid - check the National Grid ESO scenarios

- Pessimistic scenario (Steady Progression) has 6 fold increase in offshore wind production

- Movement towards heat pumps / more efficient use of energy generally

- Expansion in electrification on demand side

- Optimistic scenario (Consumer transformation) has use of H_2 as an energy store

- Wind is the main energy player in the UK

1 Generation

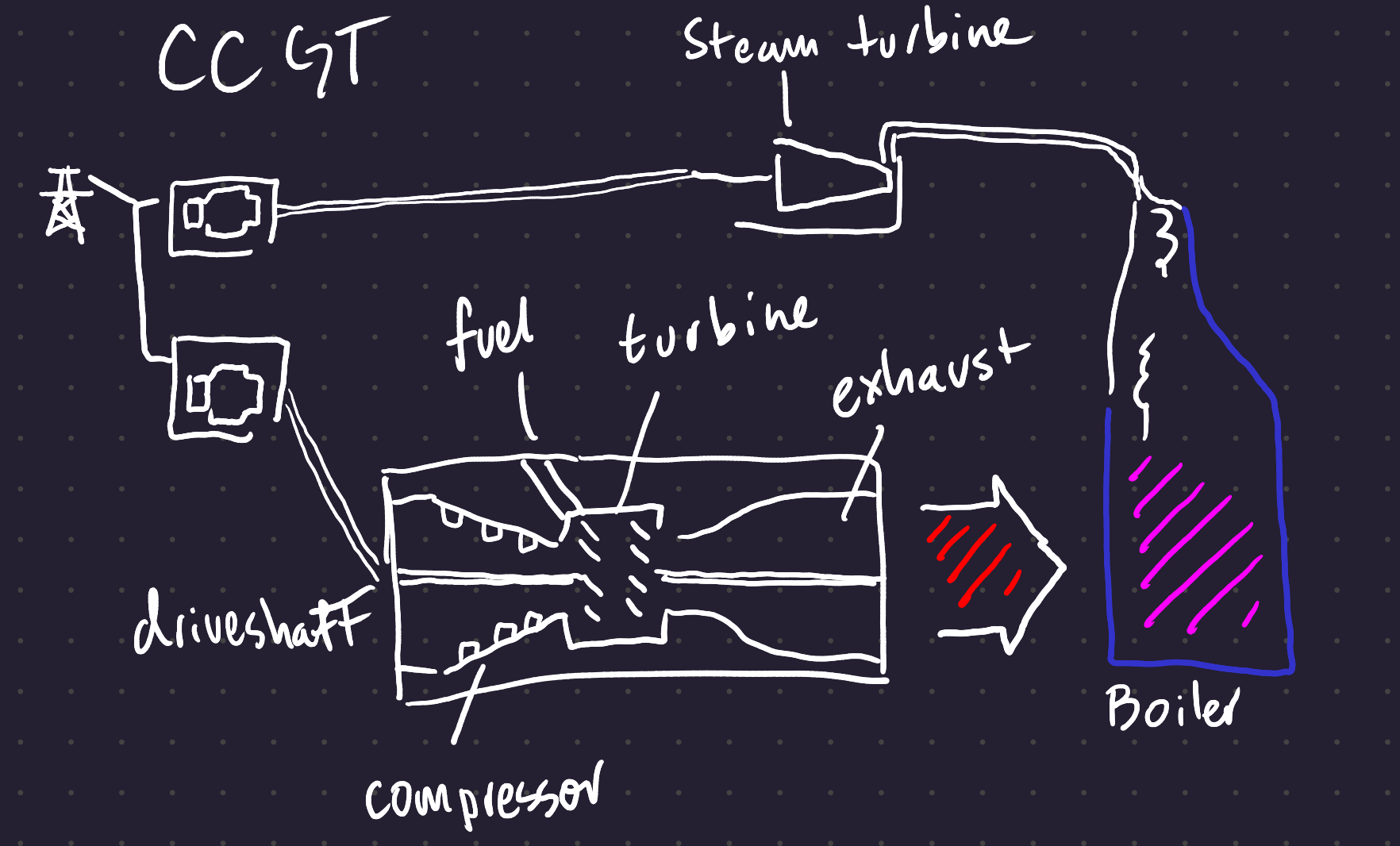

1.1 Gas generation: Combined Cycle Gas Turbine

Virtually all gas generation systems in the UK use CCGT (extremely similar to the turbine in a commercial jet airliner)

Gas combusts in combustion chamber, creating mechanical energy with 50-60% thermal efficiency.

Combined cycle: You use the hot air to drive a boiler, producing steam, driving another turbine. The engine turns one generator and the boiler recovers some energy.

1.2 Nuclear Generation

- 20% of UK generation

- Low emission, good for security of supply, small footprint

- Long and expensive construction and large environmental “concern” addressed with excessive regulation

Most of the cost of nuclear is capital expenditure (capex).

Most common type is the pressurized water reactor with 3 main water systems - reactor, steam, cooling.

1.3 Coal fired power statinos

Maximum thermal efficiency of ~40%. Coal is milled into a fine powder, combusted in a heat exchanger, and used to drve a turbine. The inefficiency is inherent in the thermodynamic cycle (you need to cool the steam to create an heat gradient that allows the steam to drive the turbine).

1.4 Wind Turbines

Typical offshore power ratings are in 4-10 MW range. 15 MW designs (larger and larger) are coming.

Onshore wind turbines are rated for 2-3 MW, and are quite small compared to offshore turbines, which are larger than an Airbus A380.

The blades in an offshore wind turbine weigh 35 tonnes and the nacelle weighs 390 - just about as large as building a small skyscraper.

Main companies: - Minyang - Vestas - GE - Siemens

Offshore wind resources are higher quality than onshore (less turbulence = greater energy extraction).

Downsides: Huge infrastructure is needed to return the electrical power to the shore (DC, massive AC)

1.5 Solar PV (photovoltaic)

Rapidly growing renewable resource, not so useful in the UK (the sun does not shine on the heart of the British Empire). Most of the increase in solar production in the UK is from subsidies, although the price of solar panels has been decreasing rapidly. Solar creates distributed supply.

1.6 Hydroelectric power

Hydro power is predictable and dispatchable. Unfortunately very geographically dependent (limited opportunity for expansion in the UK).

The 3 Gorges Dam in China produces 22.5 GW of power, about half the consumption of the UK

1.7 Tidal power

Predictable and steady power output, but currently in pilot development. UoE is heavily involved in tidal power.

1.8 Wave power

Predictable but unsteady power output. Waves create a lot of mechanical energy, and capturing that energy is a significant challenge.

1.9 Biomass

Take crops, refine them into a biofuel, combust it in a generator and drive a steam turbine. Kind of a waste of perfectly good farmland.

2 Operation

2.1 Legal Requirements

Heavily regulated to ensure interoperability &c. Sinusoidal voltage, required to be at a frequency of 50Hz +- 1%. On a given day it will oscillate between 49.9 and 50.1 Hz as different power sources come online and offline. This is caused by imbalances between the consumption and the production side.

All mechanical generators are electrically coupled through the transmission system. Thermal generation systems use synchronous machines, where the frequency of electricity generated is directly coupled to the electrical frequency. The mechanical shafts of these machines store significant rotating kinetic energy; if the frequency wants to slow down, all of the driveshafts in every generator in the UK must slow down to match, which releases a lot of energy. Similarly, increasing the frequency requires a lot of power.

Energy systems produce every single bit of power that is used the moment it is consumed. Production must match load exactly.

If P_{gen} > P_{load} \rightarrow the frequency of the system increases, extra energy goes into the driveshafts of the generators

If P_{gen} < P_{load} \rightarrow the frequency of the system decreases, extra energy comes out of the inertia driveshafts of the generators.

This is because it is difficult and expensive to store electricity: Electrical energy cannot be stored in large quantities.

Frequency Regulator: every power station has a governor measuring the system frequency, and automatically adjusting their power output based on how far from nominal that frequency is.

Every 30 minutes, human operators (dispatchers) reevaluate the energy needs; power stations adjust their power output constantly.

Different power stations can adjust at different times - most of the frequency changes are mediated by gas in the UK; they are more responsive. Wind and solar factor in not at all; “you can’t dispatch the wind.”

2.1.1 Big frequency events

August 2019: lightning struck a transission line. The frequency fell to 48.8 Hz (collapse-adjacent). 1 million customers lost power.

- Lightning trips transmission lines

- Power stations can have mechanical or electrical faults

In a big power event, loads can change by gigawatts.

Failures are often correlated, and the power system is no exception.

LFDD: Low Frequency Demand Disconnection - automated disconnection of loads to rescue power system.

To counteract major faults:

- Spinning reserves

- quicly ramp up power output in the event of a fault: gas fired plant rated for 900MW but operated up to 800MW to provide 100MW of spinning reserves

- The plant is connected “spinning” to ramp up quickly.

- Fast acting reserves

- pumped hydro, large battery systems.